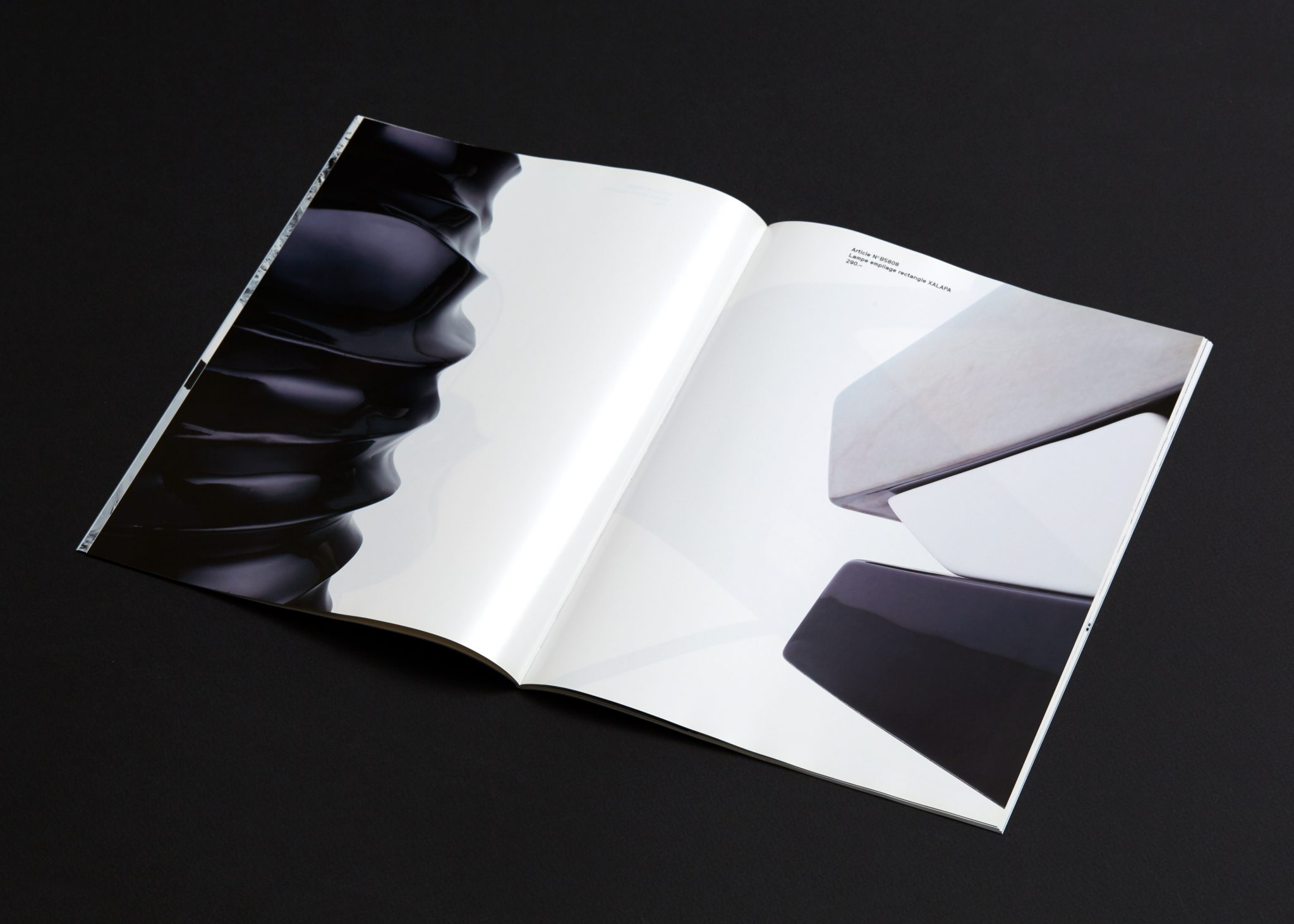

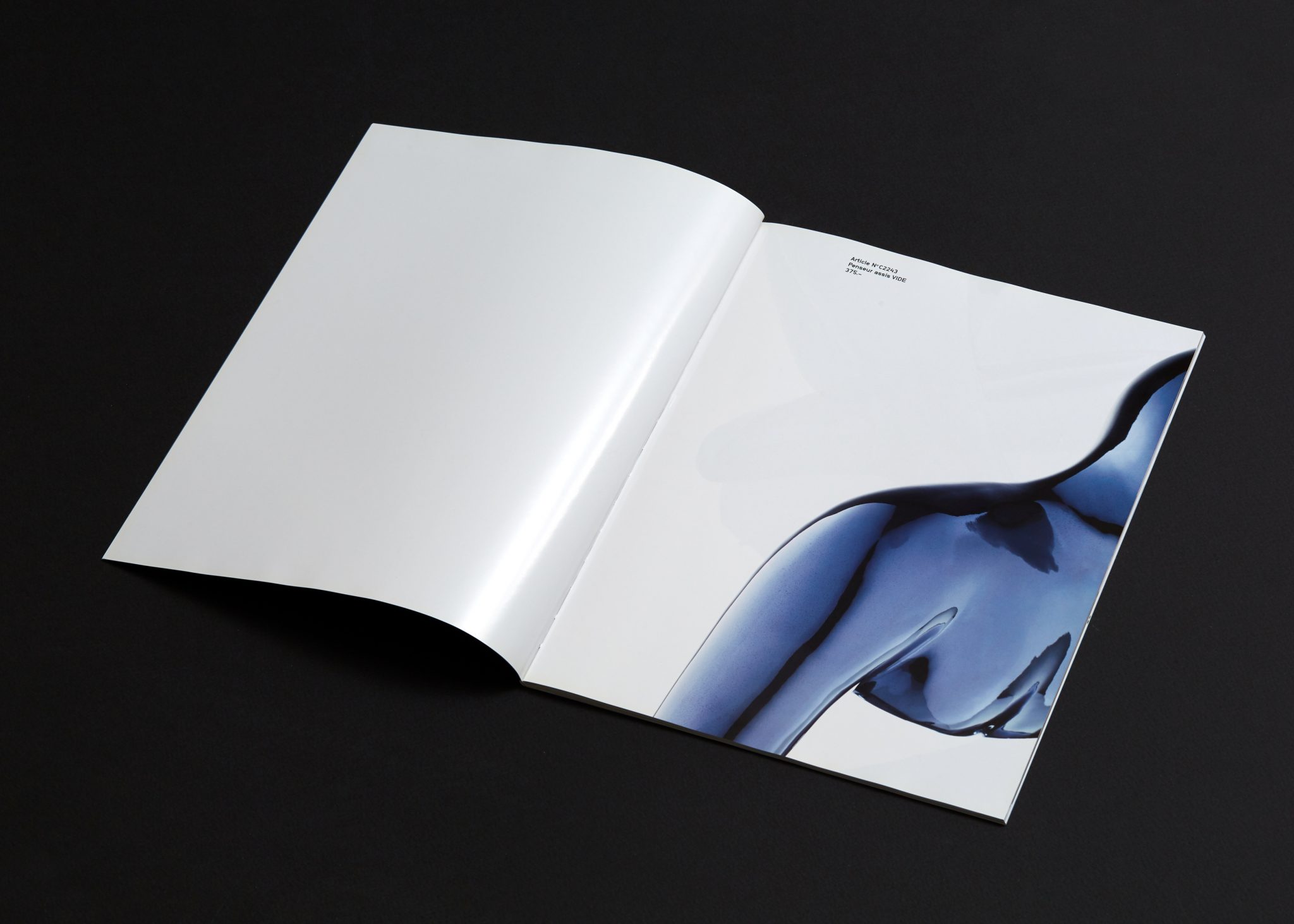

This publication was produced on the occasion of Thomas Adank’s exhibition titled Mérinat as part of the Festival Images in Vevey, Switzerland.

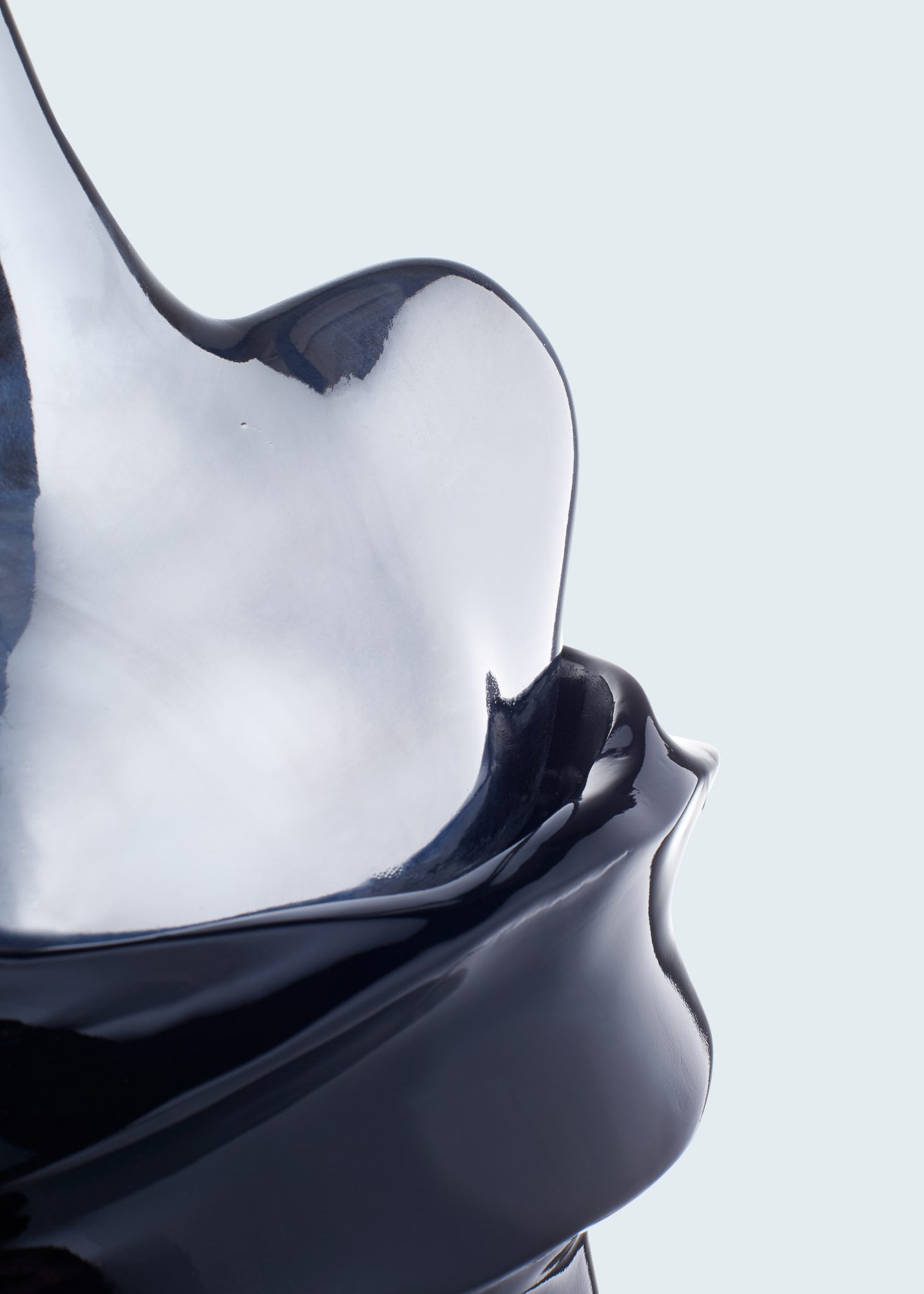

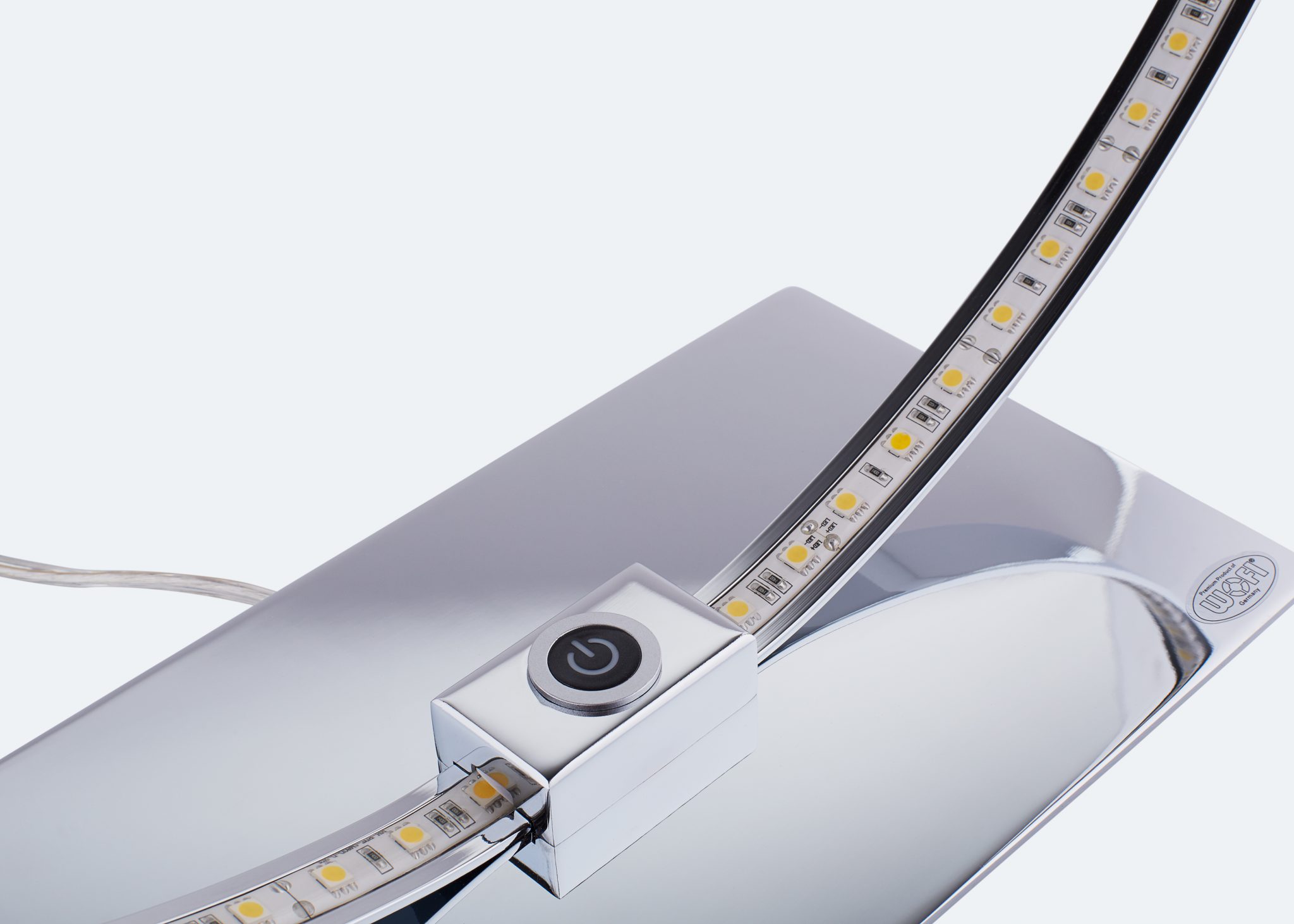

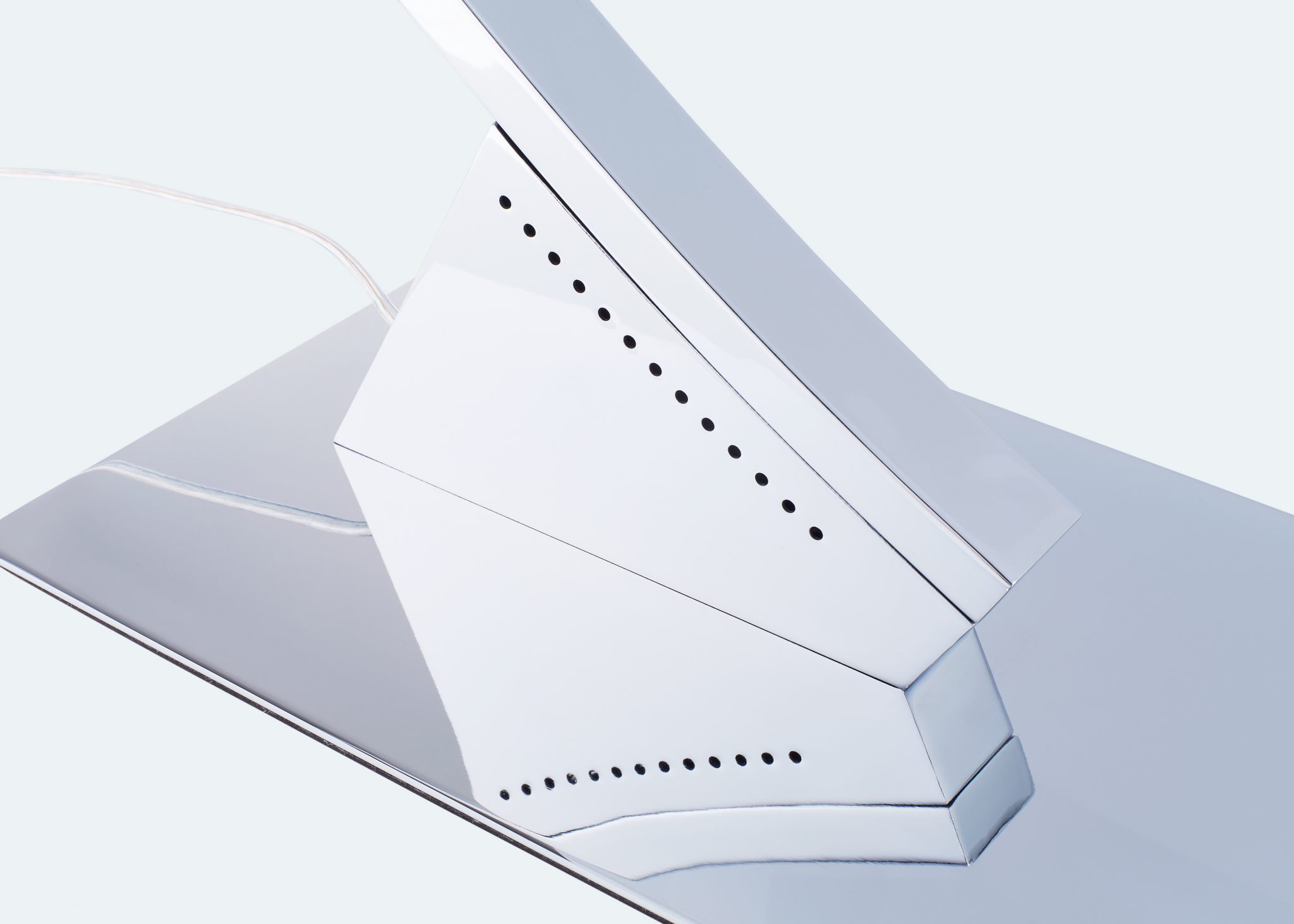

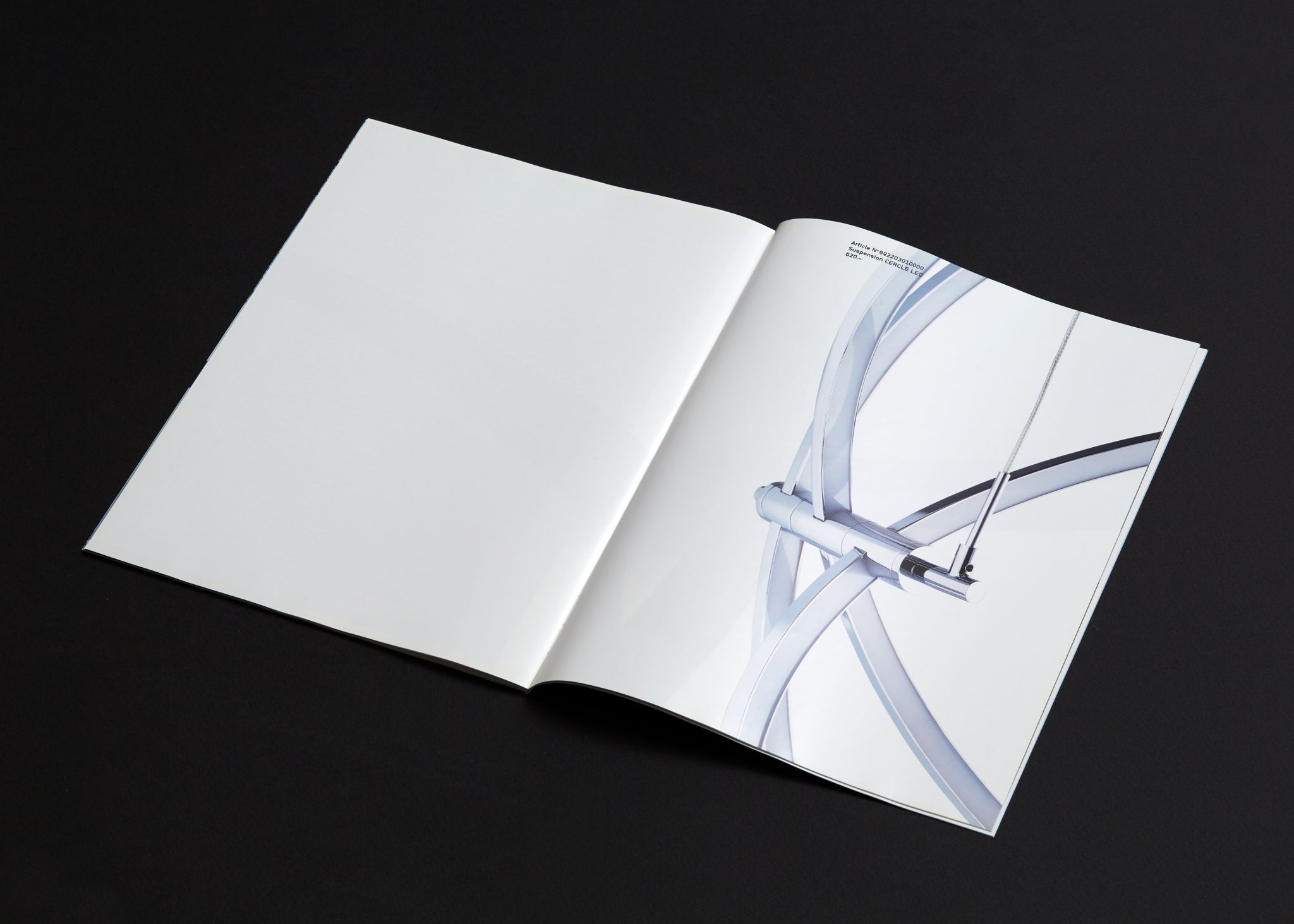

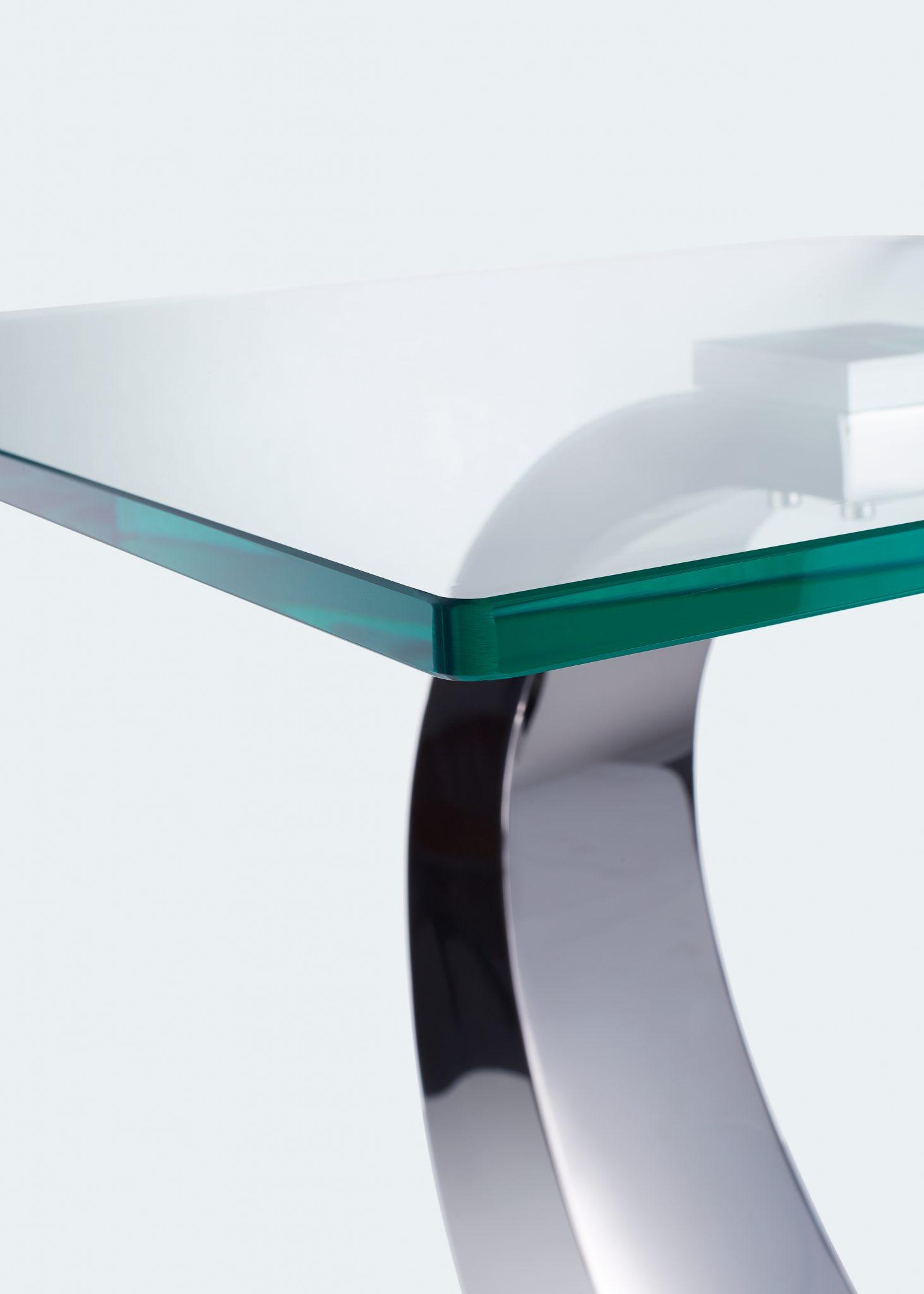

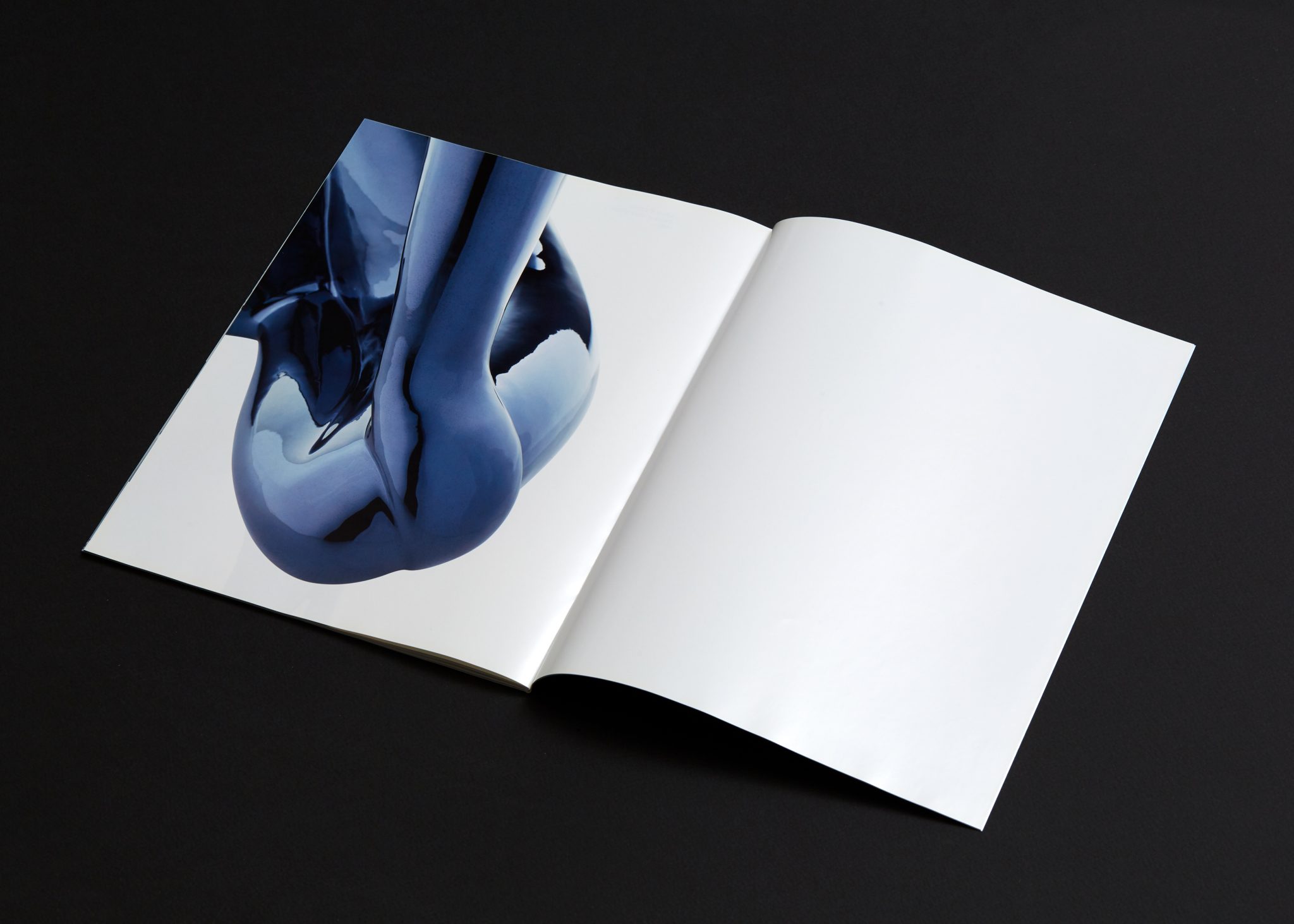

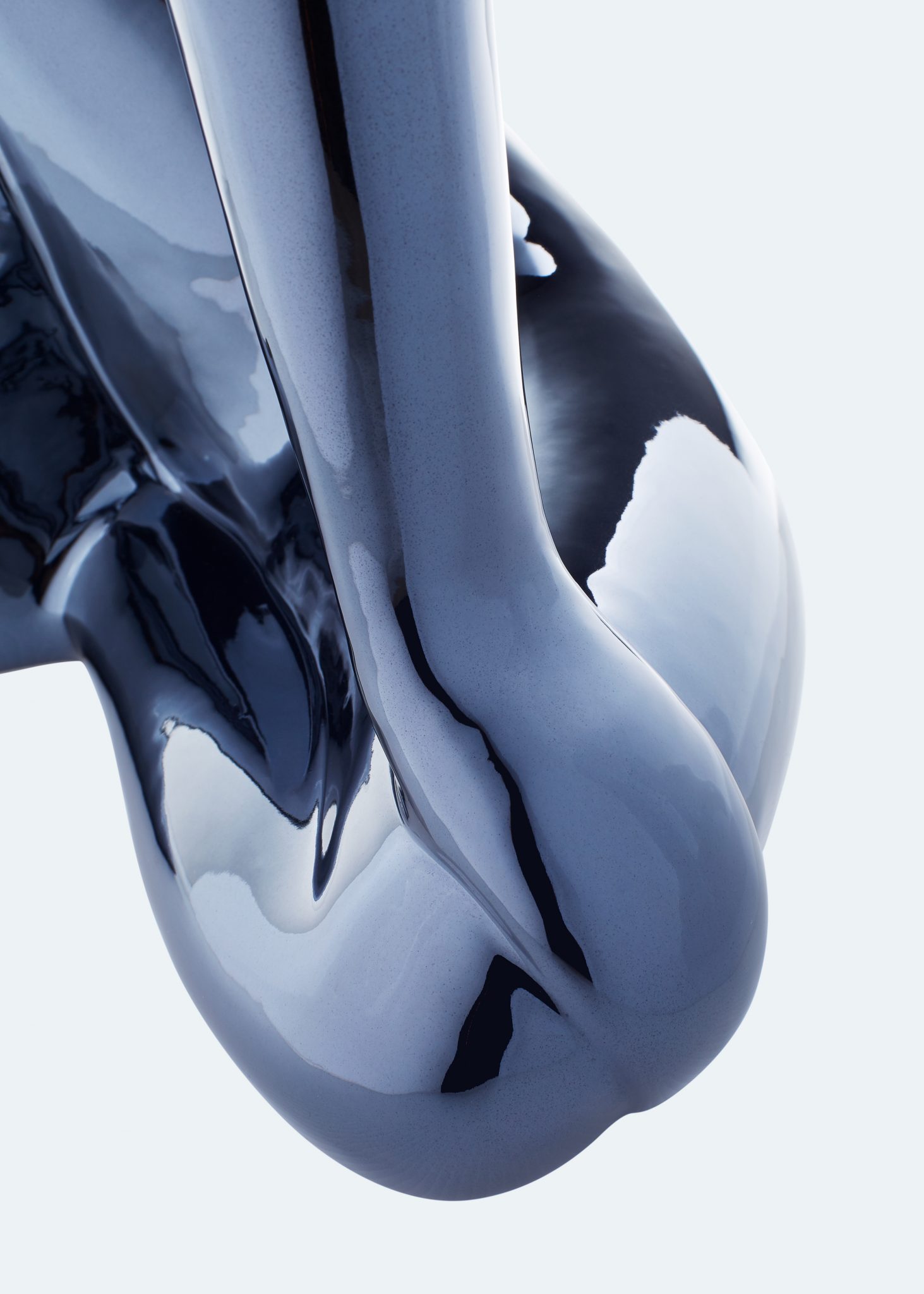

The project emulates a product catalogue for a local lighting store in the town of Vevey on the shores of lake Geneva. Using the lamps and other items for sale in the store as inspiration for the images, the project questions our relationship to artificial lighting as well as the status of commercial imagery.

Published by Images Vevey and TSAR Editions

Designed by Julien Fischer

Text by Pablo Larios

Tell us about your work surrounding theories of ‘lighting’ – is there a philosophy behind it?

Last year in the US, the borough of Brooklyn replaced the bulbs used in streetlamps to LED – a type of light technology that is comparatively cooler and is frequently described as ‘blueish’, though it is considerably more energy efficient (these bulbs have a fifteen-year lifespan) as well as brighter. In spite of the total increase in lumens at night, people immediately complained of a blue, cold screen over the streets, as if it were a ‘screen’ from an electronic product. Indeed, the bulb issues a similar kind of light to a laptop or mobile phone. Many people reported an inability to sleep, since LED lights could penetrate curtains. In Berlin today, it is still possible, when a satellite photograph is made of the city at night, to see a division in the colour of the city corresponding to the Berlin Wall. Different kinds of streetlamps were installed – one is orange-yellow and the other white in comparison.

What are you suggesting?

In these turbulent times we live in, electronics and lighting continue to be the force to unite us or to divide us, as well as to provide a space for aesthetic beauty and quiet contemplation. Lighting, a near-immaterial substance, reflects political, economic and social divisions. The simple bulb can shape our experience in intangible ways. This is a fact that photographers have always known. My work has frequently sought to describe how, since the 19th century, the proliferation of techniques of lighting and the technology of electricity have enacted changes in visual norms as well as everyday life. This era corresponds roughly to the anthropocene, or the age of man – but it is the same as when humans experienced a massive change in their sleep schedules. Since humans first invented fire, lighting has been a source of both comfort and stability. Artificial light provides a place for refuge from nature. Domestic light has often defined ‘in’ and ‘out’ – shelter from the elements – regulating a boundary between nature and culture. Lighting is something both timeless and subject to personal taste – it can add drama and intensity, or soothe and comfort. Light can reflect secular, Protestant values (consider the conspicuous display of lit interiors in Northern Europe), just as candles have, for years, been tied to religious identity and ceremony. Light can expand or make smaller the existing architecture of a space. It is primordial. The early mysticism of the first sun-worshippers is reflected in later movements – from the first wave of the Bauhaus up to today’s healing and optimization practices of Silicon Valley.

Your work has always stressed this commercial relationship. How can something as intangible as a light installation be turned into an experience? A product?

Lighting is something essential that you don’t always know you notice. You may walk into a room, and it feeds the soul, or you might walk into another, and you are left cold. They say you make a judgment call on someone within the first fifteen seconds, the first handshake… Well, in many ways it’s the same way with lighting. Yet it, too, is fundamentally not autonomous – a light-filled room says very little about that room, or the quality of light, since it depends on contrasts, shadows, collisions between different realms. As such it is fundamentally ‘Angewandt’, which means ‘to-the-wall’ – applied. Today, many individuals prefer to adapt modular settings that can be changed at will, which has led to the emerging field of home automation, itself tied into bio-feedback rhythms. In a new shift in domestic space, the home becomes matched to the rhythms of the body again – ‘sleeping’ at night, appliances off, or becoming ‘wakeful’ in moments of activity.

How to distinguish between a product and the aesthetic experience? Can the commercial be art?

In 1909, the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla painted a streetlight – the theme might seem humdrum for some, but you can see how the man-made light far outshines the crescent moon, also visible in the painting. And true, for many Modernist movements, any division between applied and ‘fine’ art were shattered. Benjamin admiringly cites Baudelaire who, visiting the city of Brussels which was not lit at night, wrote: ‘No Shop Windows, There is nothing to see… And the streets are unusable’.

What about today?

For many today, such a division is impossible and even unworthy. The corporate realm continues to draw upon art, and vice versa. Adherents of contemporary art after Duchamp have failed to recognize that the possibility of design already achieves such a total integration between art and the product. Andy Warhol was a graphic artist and illustrator in a commercial capacity, before he integrated this practice of ‘branding’ into the culture-industrial apparatus of art in his Factory. But such a product, whose value and use is immaterial and tied to a spatial experience, cannot be ‘taken home’ in a strict sense or even reproduced in the same way as a piece of art. In this way, it is important to evaluate all aspects of presentation in devising a spatial environment that is immersive and still precise. A showroom environment could be a metaphor for such a realm where object and décor, use and beauty are united – this is Benjamin’s ‘intoxicated fusion of street and interior’ and its ‘wide panoramas of light, color and perception’. Many industrial designers attempt, today, not to create ‘products’ but really to shape ‘experience’. It is likely that, in the best cases, a viewer will see no difference between a decorative, aesthetic product and a useful one – that is, an applied, commercially viable product and a product that is beautiful and appealing.

This fiction, which takes the form of an interview, was conceived by Pablo Larios for Thomas Adank’s project Mérinat.